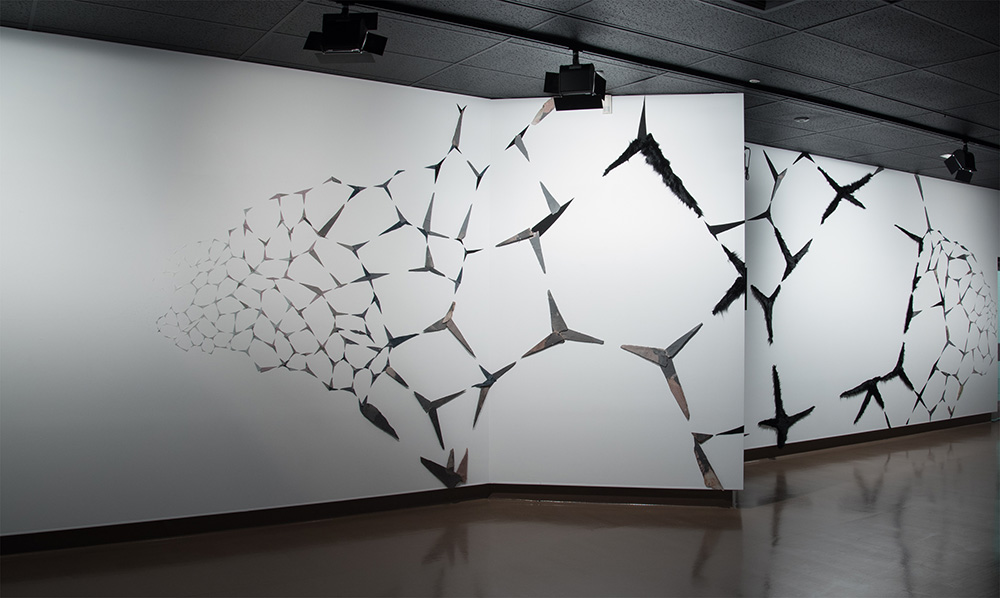

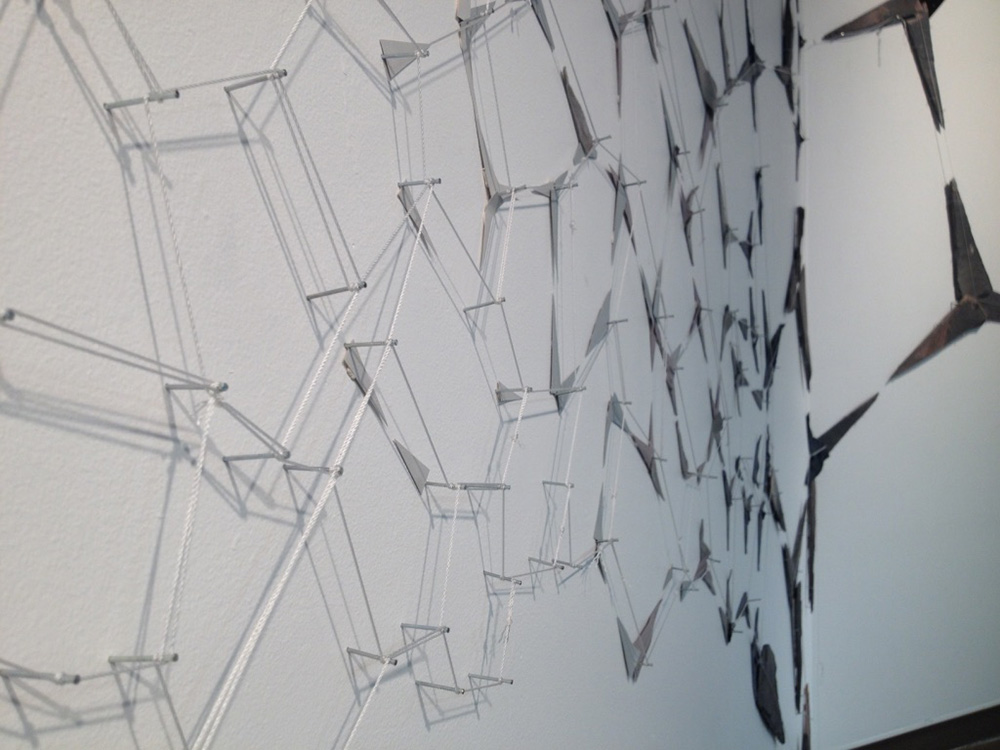

In September 2016 I held a solo exhibition at La Trobe University’s Phyllis Palmer Gallery. It was one of the first opportunities during my PhD research to demonstrate evidence of thinking in mosaic as a new mode of making, and was influential in developing the work I have made since. The exhibition title The Material and the Immaterial referred both to the materiality of mosaic and the act of making, and to the notion of immateriality; the latter being both the non-material through the absence of matter and the spiritual aspect of non-materiality. The largest work was a wall installation of the same title, and I have since made two further versions of it. This first iteration of the artwork titled The Material and The Immaterial was later developed and re-mounted at the Transitions group exhibition at the ACT Craft & Design Gallery in Canberra in March 2018. The third iteration The Material and the Immaterial #3 was the centrepiece of my final PhD examination exhibition at Lot19 Gallery in Castlemaine, July-August 2019. I will briefly explain this work. With the intention of extending my range of media and methodologies, in The Material and the Immaterial I sought specifically to overcome the three formal restrictions for conventional mosaic – of physical weight, lengthy production time and monetary expense. Through engaging thinking in mosaic and thus contemporising the use of traditional canons, I created a kind of exploded mosaic. As though a gusty wind had blown through the tesserae, lifting and separating them until the tesserae became the interstices, the wall voids between them somehow became not negative spaces but resembled positive, albeit non-physical forms. The overall effect, like a huge crescendo and diminuendo and its resulting cellular network of intersecting pentagons was made using tesserae whose material weight corresponded with their growth and subsidence in scale; using media each fixed independently to the wall, ranged from lightweight translucent paper, cardboard, woollen felt, to the more tactile materials of slate, marble and fake fur. The result was an experimental synesthetic work, something like a sound that could be seen and touched, a work to be experienced rather than an object to be mutely observed. For me as a maker seeking to overcome the conventional mosaic limitations of slowness, weight and expense, it was a fast, lightweight and inexpensive textural work. Whether or not it conformed to other people’s conventional definitions of ‘mosaic’ does not concern me, because I made it by using mosaic as a verb. All I know about form and flow derived from a lifetime of work as a mosaicist, was employed. It was the result of thinking in mosaic. Like any mosaic this work was made using many individual components, which now sit cleanly packed into boxes ready for their next installation, iteration #4. I welcome thinking in mosaic as a means of practicing an individual work to make it the best it can be, perhaps the way a singer sings a song not just once, but many times.

Mosaic Artist Helen Bodycomb