Ancient Mosiacs

And their Conversation with the new

I liken Greek and Roman Mosaics to really good red wine. The first swig is never the tastiest, but as the palate acclimatises great depths of beauty are revealed. There is much I admire about ancient mosaics, on many levels.

The logic and elegance of andamento – the directional laying of tesserae to render form, and the visual vibrations of opus vermiculatum graphically projecting and animating otherwise flat and silent subjects, are inspired.

It is a mistake of the post-industrial era that some consider mosaic as (in part) a neatness competition. Whilst slovenly construction can impair image clarity (and frequently compromises structural integrity), the wonderful softness of the handmade and the imperfect is what gives life to mosaics. This softness gives the mosaics room to breathe.

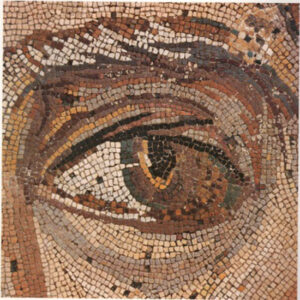

(Museum of El Djem, mosaic detail from the triclinium of The House of Africa)

Near constant volcanic earth movements across the north of Africa and the Mediterranean have further visually softened many ancient mosaics, creasing and bending, sometimes crushing and swallowing them again within the earth (protecting them). The ancient lime mortars are capable of re-knitting small ruptures, as the calcium carbonate is exposed to moisture and self-heals. Ancient sub-floor preparations were often metres deep – with layers of lime, volcanic powder from the Greek island of Santorini, marble dust, pebbles and brick fragments – or in North Africa, sometimes they were simply laid over large sections of hard stone with minimal substrate construction. It is almost inconceivable to think that mosaics made using the latex polymers of today will survive another 2,000 years.

Eroticism, both explicit and implied are common themes in Roman mosaics. In the above work, whilst the tonality of the basket and its fruit describe lusciousness and the sculptural form of the fruit, their arrangement is symbolic – there is no attempt to render them as three dimensional still life objects. Their role is metaphoric, they are both food and fecundity. Astute choices have been made by the Pictor Imaginarius about what to amplify and what to tone down, rather like a sound

engineer twiddling the knobs on the mixing desk to arrive at the most desired acoustic result. This highly discerning taste is evident across thousands of mosaics we are fortunate to enjoy 2 millennia after they were made.

Navels are rendered like seashells. Demure, elegant, softly rounded (no fast food muffin-tops here).

High levels of detail are rendered where important, in this work giving Japanese manga artists a head start 2,000 years later.

The symbolic beauty in this work lies in the exquisitely detailed rendering of the Greek warriors’ musculature and the attention to fine detail in their legs and feet. This acts as a segueway to the story of Philoktetes (with whom the warriors are talking). Philoktetes, having suffered a serious foot wound which smelt so bad he was abandoned whilst en route to the battle of Troy, is here being entreated to rejoin the battle and take Troy.

One of my favourite contemporary mosaicists – who also revels in the ancient – is Chicago artist Jim Bachor. His version of a Roman mosaic depicting feet and footwear, Evidence of Nike, is a witty melding of the ancient and the modern.

“Trying to leave your mark in this world fascinates me. Ancient history fascinates me. Working on an archaeological dig in Pompeii in 2001 melded these two interests for me when I discovered mosaics. In the ancient world, mosaics were used to capture images of everyday life. Those colorful pieces of stone or glass set in mortar are the photographs of empires long past. They do not fade.”

Jim Bachor – Evidence of Nike, 2010

Jumping forward just a few hundred years from the latest roman mosaics, the links between antiquity and modernity continue to resonate for me.

On the outskirts of Ravenna (Italy), lies undoubtedly my favourite early Christian Basilica, St Apollinare in Classe. Created during the Christian middle ages, the spectacular mosaic artworks adorning the vault and apse were made during a time widely recognized as the golden age of mosaic. It was the Byzantine era, the time of the christianisation of Europe, and a period when Ravenna’s naval fleet of no less than 250 ships were moored literally at the doorstep of St Apollinare in Classe.

The mosaics represent the transfiguration of Christ and feature a central dominant cross (the Saviour) above a praying Saint Apollinaris (after Passio Sancti Apollinaris – the first Bishop of the city). Apollinaris stands flanked by the three apostles Peter, James and John – depicted as three lambs gazing up at the Saviour. In what always appears to me to be the most audacious of skies, the polychromatic clouds conveniently change direction at the emergence of Moses (on the left) and Elijah (to the right) and continue at right angles to their point of origin; an inspired solution to a design challenge within a dome.

Below them lie the garden of Gethsemane, in which gorgeously lush, almost modern cartoon-ish rocks and foliage are suggestive of American writer Dr Seuss’s truffula trees.

In the same Basilica, flanking the apse are the winged depictions of the four Evangelists. Of them, Luke (portrayed as the bull) has always intrigued me, with the folding of facial planes pre-dating the cubists by 14 centuries!

Back to Ravenna and the loveliest of stylized transparent mosaic waters is rendered in The Arian Baptistry, where the artworks within the dome describe the baptism of Christ in the River Jordan.

One of the most eloquent installations I have ever observed involving the ancient and the modern was CACO3’s installation Immersione during the International Mosaic Festival Ravenna Mosaico in 2011. The monochromatic mosaic resembling a large bath towel draped over a stand (as if to dry Christ following his baptism) was far from blasphemous or ill-placed. Immersione was graceful and quiet, perfectly complimenting the colourful and formal early byzantine mosaic fresco above it.

CACO3 is a three way collaboration between mosaicists Aniko Ferreira da Silva, Giuseppe Donnaloia and Pavlos Mavromatidis. These young artists who studied together at the School for Restoration of Mosaics in Ravenna are successfully applying ancient methods with contemporary intent. Just as the byzantine mosaicists manipulated the setting angles of the tesserae to maximise the refractive qualities within the mosaic (especially utilising the gold leaf tesserae), CACO3 use a markedly exaggerated incline on monochromatic tesserae to express notions of change in natural phenomena.

Immersione was an apt and clever contemporary work, completed by its environmental context; a perfect conversation between the old and the new.